At a Glance

- The High Seas Treaty became legally binding on Saturday, creating the first global framework to protect marine life beyond national waters.

- The pact covers nearly half the planet’s surface and mandates environmental impact assessments for harmful activities.

- 83 countries have ratified so far, including China and Japan, while the U.S. has signed but not ratified.

- Why it matters: The treaty is the only path to hitting the 30% ocean protection by 2030 goal scientists say is critical for climate and biodiversity.

The most sweeping ocean conservation agreement in history officially became law Saturday, opening nearly half of Earth’s surface to coordinated protection for the first time. The High Seas Treaty, finalized after almost two decades of negotiations, sets rules for environmental reviews, marine protected areas, and sharing of ocean resources in the 64% of the ocean that lies outside any single country’s control.

What the Treaty Requires Starting Now

Countries that have ratified the pact must immediately begin joint work on ocean science and technology. Companies planning activities that could harm marine life-from fishing to potential deep-sea mining-must carry out environmental impact assessments that meet the treaty’s standards.

Researchers hoping to commercialize organisms collected on the high seas, such as for new medicines, must notify other nations and share findings. Perhaps most importantly, governments must now promote conservation when they sit on other international bodies that regulate shipping, fishing, or seabed mining.

Marine Protected Areas on the Horizon

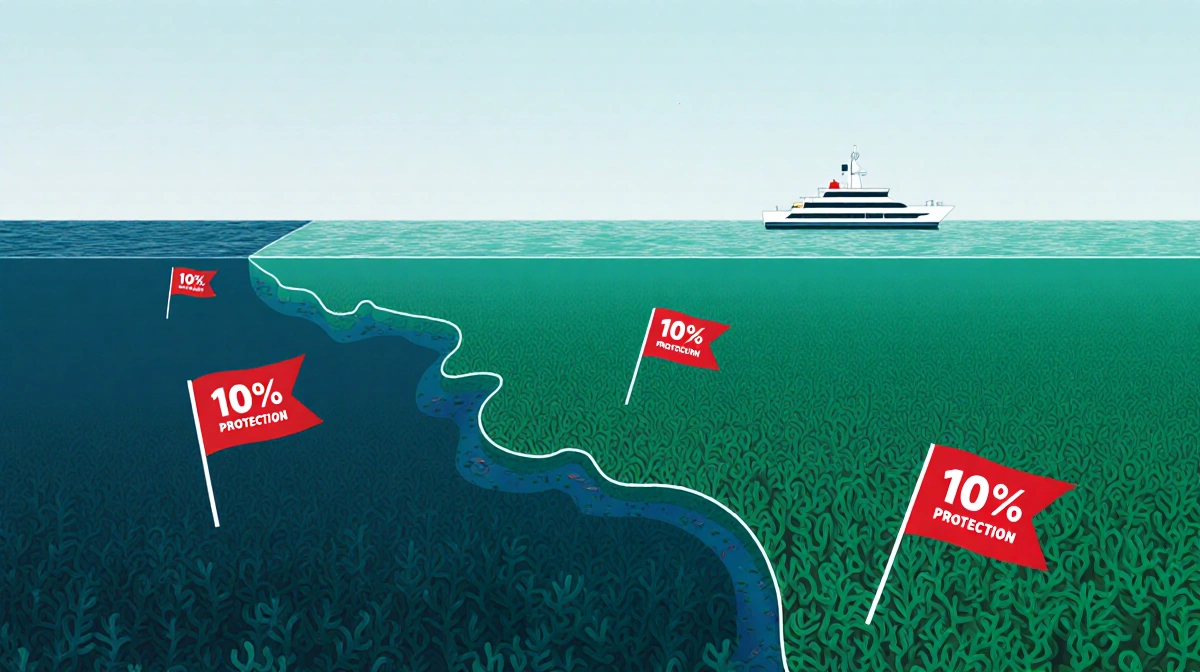

The treaty empowers governments to propose vast new protected zones in international waters, which make up about two-thirds of the global ocean. Currently, only 1% of these areas enjoy any protection.

Potential early candidates include:

- Emperor Seamounts in the North Pacific

- Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic

- Salas y Gomez and Nazca Ridges off South America

Approval of the first sites will wait until the second Conference of Parties, since the scientific review body has yet to be formed. The inaugural Conference of Parties must still decide budgets, committee structures, and other operational details within the next year.

Pressure to Hit the 2030 Target

Conservation groups warn governments must move fast to achieve the global goal of protecting 30% of oceans by 2030. Because the high seas account for such a large share of marine space, their protection is indispensable.

“The marine protected areas under the treaty will only be as strong as the governments make them,” said Megan Randles, global political lead for Greenpeace’s Ocean Campaign. “We can’t trust big fishing industry players to simply stop fishing in these critical ecosystems. We need governments to use the treaty to force their hands.”

How those areas will be monitored and enforced remains undecided. Countries are weighing options from satellite surveillance to joint patrols and assistance from other UN agencies, according to Rebecca Hubbard, director of the High Seas Alliance.

U.S. Sits on the Sidelines

The United States has signed but not ratified the agreement, leaving it able to participate only as a non-voting observer. Under international law, signatories are expected to comply with treaty objectives even before formal ratification.

“The High Seas Treaty has such incredibly broad and strong political support from across all regions of the world,” Hubbard said. “Whilst it’s disappointing that the U.S. hasn’t yet ratified, it doesn’t undermine its momentum and the support that it has already.”

A Rare Win for Global Cooperation

Advocates frame the treaty as proof that environmental protection can still unite nations despite geopolitical tensions.

“The treaty is a sign that in a divided world, protecting nature and protecting our global commons can still triumph over political rivalries,” Randles said. “The ocean connects us all.”

The pact entered into force 120 days after the 60-country ratification threshold was crossed in September. As of Friday, 83 nations had formally joined, with major maritime powers China and Japan among the latest to ratify.

Key Takeaways

- The High Seas Treaty is now legally binding for ratifying countries, covering nearly 50% of Earth’s surface.

- Immediate obligations include environmental impact assessments, shared research, and promoting conservation in other international forums.

- The first marine protected areas could be approved at the second Conference of Parties, following scientific review.

- The U.S. remains outside the voting membership, though it can observe and is expected to follow treaty objectives.

- Conservationists say swift implementation is essential to meet the 30% ocean protection target by 2030 and to safeguard critical ecosystems such as coral reefs that provide an estimated $2.7 trillion annually in food, medicine, and economic services.

___

Megan L. Whitfield reported this story. News Of Fort Worth published it. The Associated Press receives support from the Walton Family Foundation for coverage of water and environmental policy. The AP is solely responsible for all content.