At a Glance

- A twentysomething writer admits total dependence on her iPhone, calling it an extension of her body

- Her friend Lilah ditched smartphones for a “dumb” device, feeling her “brain was being consumed”

- The extended mind hypothesis suggests phones function as part of our cognitive system

- Why it matters: The psychological bond with devices raises questions about whether true digital separation is possible

The struggle to unplug has never felt more real. While some young adults romanticize life without smartphones, the reality of severing that digital tether proves far more complicated than simply switching to a basic device.

The Crunchy Friend Who Escaped

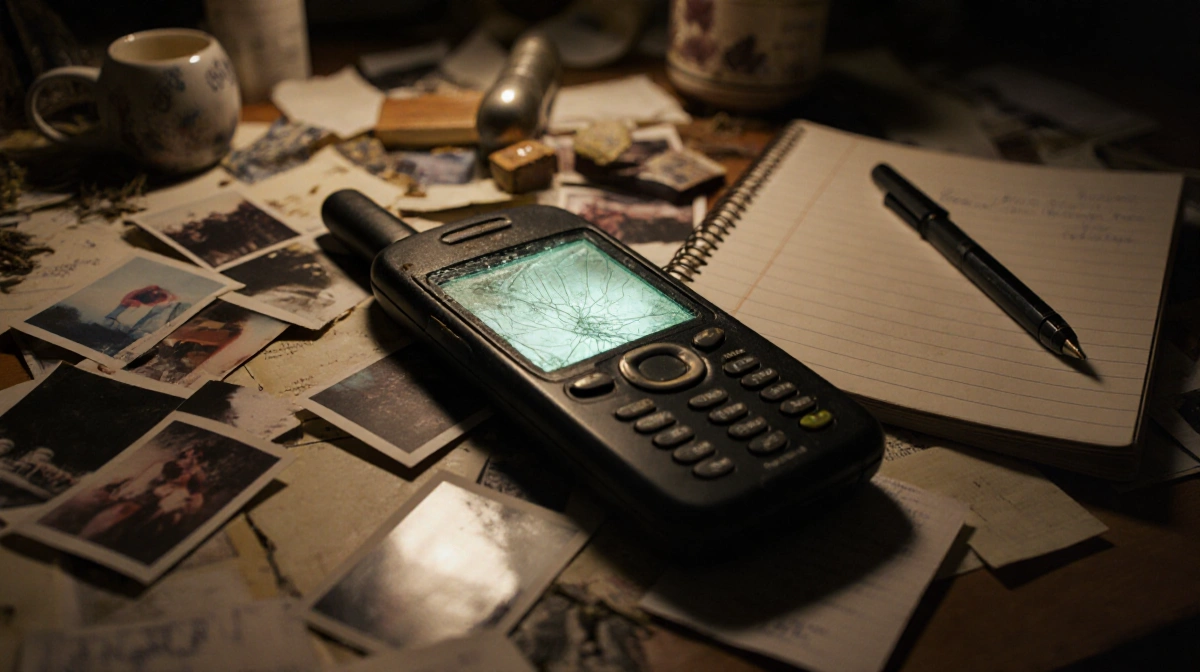

Lilah represents the ideal many millennials chase. She once lived in a yurt, made homemade wine, and refused to kill bugs. After graduate school, she traded her iPhone for a dumbphone that connected to Wi-Fi but blocked internet and apps. “I think my main reason for getting rid of it was that I felt like my brain was being consumed,” she told Cameron R. Hayes.

The transition wasn’t entirely voluntary. A university administrator had previously forced her to own an iPhone for two-factor authentication tied to her student duties. Upon graduation, she celebrated by returning to a simpler device.

The Writer’s Digital Prison

The author wastes hours daily scrolling through videos of strangers until her eyes sting and head aches. She ideologically supports withholding data from corporations and escaping constant advertisements. Yet she remains trapped, terrified of life without her smartphone.

“Ditching my smartphone would be completely disorienting,” she admits. “It would significantly reduce my overall competence.” The panic she feels when separated from her device feels existential, as if pieces of her physical body are missing.

This isn’t mere addiction. Andy Clark and David Chalmers’ 1998 “extended mind hypothesis” suggests external tools can extend the biological brain. Checking Notes for grocery lists or using Google Maps creates a single cognitive system combining both phone and brain.

When Memories Vanish With Photos

The author’s dependence runs deeper than convenience. During senior year of high school, she failed to backup months of data while replacing her device. Photos from that school year disappeared permanently. What shocked her more: those digital memories had become her actual memories.

“My memories of that period disappeared along with them-a road trip across the South, a friend’s dramatic breakup,” she writes. “I knew, intellectually, that these things had happened. But I had no real feeling for them, no specific images to trigger my recollection.”

The Relationship That Replaces Human Bonds

Daniel Wegner’s 1985 theory of transactive memory describes how intimate couples store information collectively, functioning as a joint memory system. The author recognizes this pattern in her relationship with her iPhone, acquired at age 14.

Over years, her mind fused with Apple’s operating systems. The phone became not just a tool but part of her cognitive infrastructure, storing memories, knowledge, and capabilities she no longer maintains independently.

The Unanswerable Question

The central tension remains unresolved. While Lilah successfully severed her digital dependence, the author questions whether such un-enmeshment is worthwhile or even possible for those whose identities have fused with their devices.

The extended mind hypothesis suggests her relationship with technology isn’t pathological but evolutionary. Her phone genuinely functions as part of her cognitive system, making separation feel like losing pieces of herself because that’s precisely what’s happening.

Yet the psychological cost of this integration weighs heavily. Hours lost to scrolling, sleep sacrificed to screens, data harvested by corporations-these trade-offs increasingly trouble young adults seeking meaning beyond digital consumption.

Key Takeaways

The smartphone dilemma reflects deeper questions about human evolution in digital age. While some successfully escape to simpler devices, others find their cognitive systems too thoroughly integrated with technology to separate without significant psychological disruption.

The choice between digital simplicity and technological integration involves more than willpower-it requires understanding how deeply these devices have become extensions of our minds and memories.