Auto-brewery syndrome makes people drunk without a sip of alcohol. A new study maps the exact bacteria and biological pathways driving the rare disorder, pointing to stool tests and fecal transplants as future fixes.

At a Glance

- Gut microbes Klebsiella pneumoniae and E. coli convert carbs to ethanol during flare-ups

- Stool samples from patients produced markedly more alcohol than controls

- One patient stayed symptom-free for 16 months after a second fecal transplant

- Why it matters: Reliable diagnosis and targeted therapy could end years of legal, medical, and social turmoil for sufferers

The Hidden Brewery Inside Patients

People with auto-brewery syndrome (ABS) can reach blood-alcohol levels that mirror binge drinking even if they have swallowed nothing stronger than bread or pasta. The condition stems from gut microbes fermenting carbohydrates into ethanol that then enters the bloodstream. While everyone’s digestion creates trace amounts of alcohol, ABS pushes concentrations high enough to trigger slurred speech, poor coordination, and failed breathalyzer tests.

Diagnosis is maddeningly elusive. The gold-standard method-closely monitored blood-alcohol testing-is rarely available outside specialized centers. Many patients drift for years, accused of secret drinking, battling unexplained symptoms, or facing drunk-driving charges they swear are impossible.

Mapping the Microbial Culprits

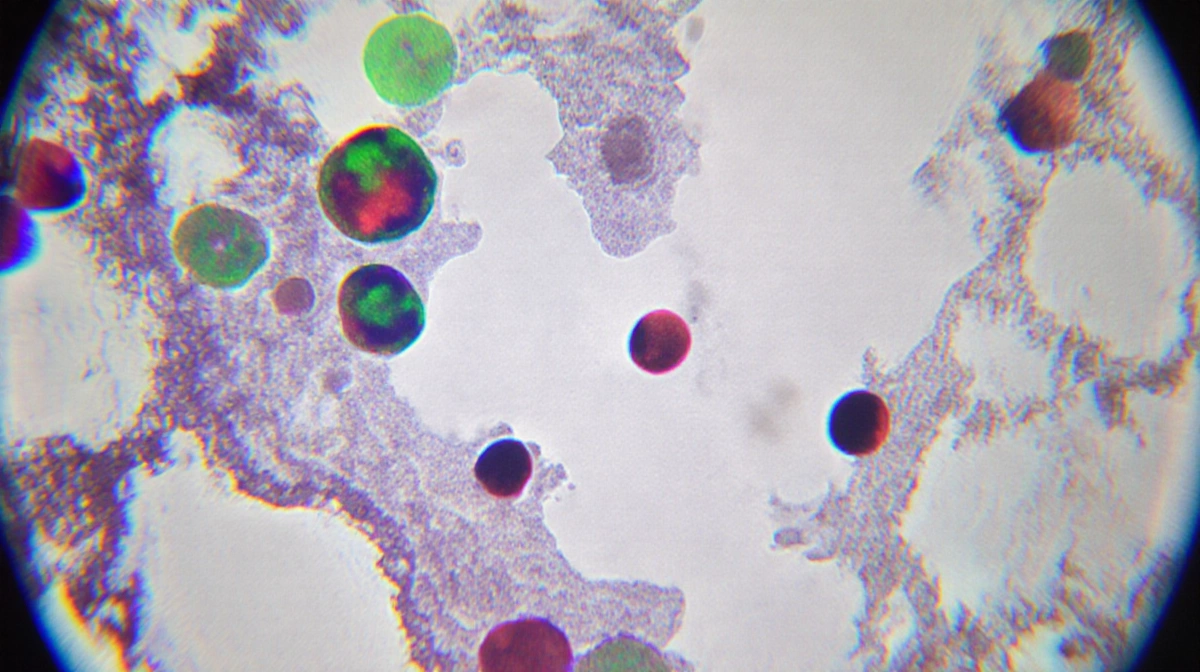

Researchers at Mass General Brigham analyzed fecal samples from three groups:

- 22 ABS patients during flare-ups

- 21 household partners sharing diet but no symptoms

- 22 healthy controls

Flare-up samples generated ethanol at dramatically higher rates than those from either comparison group, suggesting a stool test could replace invasive blood monitoring.

Sequencing revealed that Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae dominated during episodes. These strains carry enzymes tied to fermentation pathways, allowing them to churn out alcohol in the anaerobic environment of the colon. When symptoms quieted, both microbial load and enzyme levels dropped.

Transplant Turns the Tide

The team documented one patient whose life had become a revolving door of intoxication, antibiotics, and relapse. After a first fecal-microbiota transplant failed, clinicians combined a second transplant with a tailored antibiotic pretreatment. The result: complete remission lasting more than 16 months.

Microbiome tracking showed that the patient’s relapse and recovery mirrored shifts in the same bacterial strains and metabolic activity identified in the larger cohort. The findings, published Thursday in Nature Microbiology, supply the strongest evidence yet that ABS is a definable biological disorder rather than covert alcohol abuse.

Elizabeth Hohmann, co-senior author from the Infectious Disease Division, said the work could “lead the way toward easier diagnosis, better treatments, and an improved quality of life for individuals living with this rare condition.”

Next Steps Toward a Cure

News Of Fort Worth‘s investigation highlights that pinpointing patient-specific triggers remains labor-intensive. Each individual’s microbial fingerprint is unique, so future therapy may involve personalized cocktails of beneficial bacteria rather than off-the-shelf probiotics.

Hohmann is already leading a follow-up trial exploring fecal transplantation in additional ABS volunteers. If larger studies confirm safety and durability, the procedure could join a short list of accepted treatments for the once-mystifying syndrome.

Key Takeaways

- ABS is driven by identifiable gut bacteria, not deception or mental illness

- A simple stool test could replace cumbersome blood-alcohol monitoring

- Fecal transplantation offers a potential long-term fix, with one patient symptom-free for over a year

- Ongoing trials may cement microbiome therapy as standard care